Northwest Coast Indian Tribes & Their Art

Little is known about the sculptural art of the Indians of the Pacific Northwest prior to the coming of the first explorers from Europe. Archaeological evidence indicates stone carvings and petroglyphs but little wood carving, although wood was the primary material used in carving. Wood does not last in the humid environment

of this coast. Among the wooden objects the early explorers found were some roughly carved house posts and elaborately decorated boxes, masks and other

ceremonial items, but not in the quantities or quality seem subsequently. With

the coming of the whites, and with them iron tools and the riches of the fur

trade, the art of caring in wood flourished greatly. Disease also came with

the whites. Later, as the Canadian and American governments took over, both,

in conjunction with the churches, methodically destroyed the Indian culture

and society in tribes already decimated by disease. Consequently the art lost

its vitality, and the skills involved were not generally passed to the younger

generation. The basis for maintaining the structure of the society was the potlatch

system, which determined status and rights. Potlatches are ceremonial gatherings,

hosted by individuals or groups, which provide an opportunity to claim rights

and have these rights affirmed by the community, and to maintain or acquire

status. Status was not a matter of material wealth or raw power, but rather

of recognition and acknowledgment by the populace. The potlatch required much

in the way of wood carving. Many rights involved dances and songs, necessitating

masks, and the associated feasting needed food bowls and grease bowls, as well

as spoons and ladles. Status could be declared by erecting a totem pole, which

had to be carved. Much wealth was expended in preparation for a potlatch, in

carving poles and masks, in gathering gifts to be given away to those who attended,

and in preparing a feast for all.

The fur trade, particularly in sea-otter skins, initially provided the economic

basis for greater and more elaborate potlatches. Iron tools made it possible

to carve large totem poles, which became the monumental art of the 19th century.

Scrimshaw work was developed to gain more wealth, first for trade with the fur

traders, and then for general sale to settlers and tourists. On this basis Indian

art developed rapidly during the 1800's, despite the toll of disease. It was

at its peak from about 1850 to 1900, but then decreased abruptly and lost its

vitality and purpose almost totally as white settlement increased. Not only

did disease increase, but also the power of government and the accompanying

churches increased, and was systematically used to destroy the culture and self-respect

of the Indians. Potlatching was prohibited by the Canadian government in 1884,

and by the U.S. government in 1913. Schools were set up, run by churches or

government, to take children away from their families and home areas. The children

were given little education, forced to speak only English, and often physically,

mentally, and sexually abused.

While all the coast Indians potlatched and produced art, the experience during

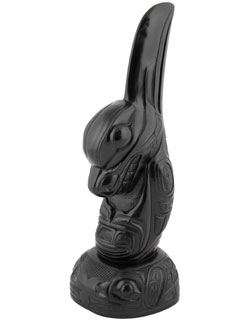

this period varied by tribe. The Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands, who developed

the most outstanding carving, were most affected by contact with the whites

and eventually lost almost all their culture and viability as a people. They

had been well located to enter early into the lucrative trade in sea-otter furs,

and were aggressive, the dominant group in warfare, and as such were able to

travel up and down the coast with impunity. They also developed the scrimshaw

trade profitably, both because they were the only group able to offer carvings

in argillite, the soft stone found only in a local deposit, and because they

were able to trade readily as far south as Victoria and Vancouver. Their totem

poles were among the finest produced. The Haida, however, because of their early

and extensive contacts with whites suffered worst from smallpox, measles, venereal

disease, and alcohol. From an estimated population of 8,000 to 12,000, at their

low point they dropped to about 800 individuals, many if not most of mixed blood.

Those tribes with less contact suffered somewhat less, but still disastrously.

The Tlingit, the northern branch of the Haida in Alaska, were less well situated

for the fur trade. They were prohibited from potlatching in 1913, later than

the tribes in Canada, and the prohibition was lifted earlier, in 1934, while

potlatching was within living memory. They kept up scrimshaw work in the form

of small wooden totem poles and grease bowls, and engraved silver bracelets,

but lacked the more profitable argillite.

The Tsimshian, on the mainland east of the Queen Charlotte Islands, were among

the earliest to erect totem poles but benefited less from the fur trade or scrimshaw

trade. As with the other tribes, fishing was the basis of their economy.

The Nootka, now known as the Nuu-cha-nulth, on the west side of Vancouver Island,

were major participants in the early fur trade, but were wracked with internecine

warfare, and so had little wealth for potlatching, and developed little scrimshaw

work or art. The Salish, on the southern end of the region, away from the centers

of art development, benefited little from either fur trade or scrimshaw.

The Kwakiutl, on the west side of Vancouver Island and on the mainland, preserved

their art and culture better than the others. They had less benefit from the

early fur trade, and little from scrimshaw, but maintained a viable fishing

industry. While they too were weakened by disease and oppressed by both church

and government, they appear to have had at times more enlightened government

officials in charge. Their villages and fishing camps were spread over a wide

area of coastal fiords, and they continued to potlatch unobtrusively in remote

locations where they could avoid the police. While they were unable to continue

to erect totem poles, they continued to carve masks and other ceremonial items,

and so maintained continuity in the skills of the art.

Subsequent to the Second World War the Indians, with the opening up of society

during the war, recognized that they could establish their rights and improve

their situation. At the same time the museums, art circles, and the general

public began to realize the loss of the unique art and culture of the Indians.

The Canadian government lifted the prohibition against potlatching in 1951.

Mungo Martin, a Kwakiutl with traditional carving skills, was employed for totem

pole restoration and to teach others. The Canadians also set up a school for

Indian art at 'Ksan, and their government passed a law allowing only the work

of Indians to be sold as Indian art. The revival in Northwest Coast Indian art

has been helped by others, such as Bill Reid, a Haida of mixed blood, who although

not taught in the traditional manner studied the classic work and produced outstanding

pieces. As a consequence, today Indians are producing classic forms and developing

new forms in a vibrant market. The art, not only in wood carving, but in other

media as jewelry and graphic art finds its place with the outside art market

and within the tribes for ceremonial use. In many communities totem poles have

been erected in the traditional manner inspired by and attesting to the renewed

self respect of the tribal peoples.

For more information ...

Please follow the links below for more information about the Pacific Northwest

Coast Indian jewelry we offer and related items.

Northwest

Coast Indian Jewelry

Northwest Indian Art & Lore

Trade

Bracelets & Rings

Jewelry

FAQs

Boma

Reproductions of Argillite Carvings & Collectibles

Totem

Poles

Scrimshaw

among the Northwest Coastal Indians

Clam

Shell Box, Detailed Views

|